In recent years, Ozempic, a medication developed to treat type two diabetes, has seen a surge in use. Due to frequent off-label usage (i.e. prescribing Ozempic for weight loss), the full extent of this drug’s side effects continues to be studied. The latest research suggests that one possible side effect of Ozempic is reduced desire to consume alcohol.

Above: Is Ozempic the solution to cure Alcohol Use Disorder? Image generated by Carlota Herrera ’27 via OpenAI.

Ozempic: A Diabetes Medication with Emerging Side Effects

Ozempic was first approved by the FDA in 2017 to treat type two diabetes. However, the drug’s frequent use as a powerful weight loss medication made its popularity soar. Ozempic—which is composed of propylene glycol, sodium phosphate dibasic dihydrate, phenol and water—slows gastric emptying and sends false neurological signals to the brain that curb hunger. These potent effects have made the drug popular with patients looking to lose weight, especially among adolescent girls ages 12-17. This off-label use in teenagers is especially concerning, as the FDA has not approved the drug for children even for its intended purpose as a diabetes medication.

Ozempic contains an active ingredient called semaglutide, a molecule that mimics the hormone glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1). GLP-1 is made by the small intestine and released into the body during digestion. Its role is to stimulate the production of insulin, therefore allowing glucose to enter cells and lowering blood sugar levels. GLP-1 signaling also slows the rate at which food leaves the stomach, and the drug sends signals to the brain that the body is satiated. To learn more about Ozempic’s composition and function, read this previously published article.

Although Ozempic’s ability to regulate blood sugar and satiety signaling has been well-documented, its ability to regulate the desire of alcohol intake has only recently gained global attention. This novel effect has been documented for a few years; in 2023, the National Public Radio (NPR) published an article citing numerous anecdotal reports that Ozempic users’ drinking behaviors changed, leading to reduced alcohol consumption after taking the drug. At that time, however, there were no clinical trials or peer-reviewed research studies to support the claims.

Since then, researchers have published several papers highlighting the relationship between alcoholism and Ozempic. Although these investigations shed light on some valuable concrete evidence, they were largely based on secondary research. However, a paper published in February provides direct evidence of Ozempic’s unintended impact on alcohol use. These studies have paved the way for further research into Ozempic’s use as a potential therapeutic for alcohol use disorder.

Alcohol Use Disorder: A Leading Cause of Death with Few Existing Drug Treatments

It’s not challenging to see why this preliminary evidence of Ozempic’s impact on alcohol use is so exciting; excessive alcohol consumption is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, claiming the lives of around 178,000 people each year. Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a medical condition that encompasses alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence or alcohol addiction. Individuals who suffer from the condition struggle to stop consuming alcohol despite negative impacts on their health, social lives and even occupational settings. The criteria for AUD are set by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), which states that a combination of genetic and environmental factors contributes to an individual’s vulnerability to AUD.

Above: Alcohol Use Disorders affect one in nearly every ten people in the U.S. Image courtesy of United States Drug Testing Laboratories (USDTL).

The World Health Organization estimates that AUD affects 400 million people aged 15 years and older worldwide. In the U.S. alone, 28.9 million people suffer from AUD. With so many people suffering from this condition, the lack of approved medicines to combat it remains surprising. Since the FDA approved the first AUD medication in 1951, only two medications, naltrexone and acamprosate, have received subsequent FDA approval to combat AUD.

New Research on Patient Data Suggests Ozempic’s Active Ingredient Reduces Alcohol Consumption

The surge of Ozempic use, coupled with high AUD rates, led to the first anecdotal reports that the drug may decrease a user’s desire to consume alcohol, prompting researchers to take notice. Many studies investigating the relationship between alcohol use and semaglutide—the active ingredient in Ozempic—have emerged as a result. However, none until now have used direct clinical results. We identified three prior studies that, at the time, further suggested a possible link between GLP-1 and AUD.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a peptide hormone which is released as a response to meal intake. Its main role is to stimulate insulin release, as well as reducing glucagon release. It also plays a physiological role as it helps regulate appetite and food intake. So, when released at digestion, GLP-1 prevents big blood sugar spikes, slows digestion and helps modulate appetite, making it an ideal active ingredient in weight-loss injections.

One of the first large-scale studies to examine this relationship analyzed the health records of 83,825 patients with obesity who had no prior diagnosis of AUD and an average age of 51. In this cohort, patients were either prescribed semaglutide (Ozempic) or non-GLP-1 receptor agonist anti-obesity medications. By analyzing their medical records, the study found that the incidence of AUD was 0.37% and 0.73% for the cohort taking semaglutide and those taking non-GLP-1RA medications, respectively.

The difference between these two rates is given as a hazard ratio of 0.5, which corresponds to a 50% reduction in risk of developing AUD. The study also investigated recurrent AUD, in which patients with a history of AUD were assessed for relapse or recurrence. The recurrence risk for semaglutide users (22.6%) was much lower than for those using other medications (43.0%), corresponding to a 56% reduction in recurrence risk.

Another study mapped the effectiveness and risks of GLP-1 receptor agonists utilizing electronic health records from the Department of Veterans Affairs, encompassing approximately 2.5 million patients who initiated GLP-1RA therapy. Although GLP-1RA is not the same as semaglutide, these compounds are the same class of medication. The study compared the GLP-1RA sample group to other patients—some receiving non-GLP-1RA diabetes treatments (e.g., insulin or oral medications)—and individuals not taking diabetes medications. Through propensity score matching, researchers found that those taking GLP-1RA had a lower risk (11%) of developing substance use disorders, including AUD.

Further research examined electronic health records from a large cohort of patients diagnosed with AUD and opioid use disorder (OUD). Specifically, researchers examined over 800,000 individuals with AUD and over 500,000 individuals with OUD. Among these, 5,621 patients with AUD and 8,103 patients with OUD were prescribed GIP and/or GLP-1 RAs. These treatments led to a 50% reduction in the rate of alcohol use and a 40% reduction in the rate of opioid use. While these studies provide evidence that decreased alcohol usage may be a side effect of Ozempic, they all relied on patient records rather than direct experimentation.

A Groundbreaking Clinical Trial Sparks Hope for the Future of AUD Treatment

To move beyond observational findings and directly test semaglutide’s effects on alcohol consumption, researchers designed a controlled clinical trial—the first of its kind to experimentally assess the drug’s impact on individuals with AUD. In his paper published in November of 2024, Christian S. Hendershot, PhD, and his colleagues sought to fill the gap in evidence by conducting a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to assess whether semaglutide could reduce alcohol consumption and cravings in adults with AUD.

The groundbreaking clinical trial placed participants in a controlled environment where they were presented with their favorite alcoholic drink. In the first 50 minutes, participants could choose not to drink and receive monetary compensation. Afterward, they were allowed to drink as much as they wanted for the next 120 minutes, and their breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) was measured every 30 minutes to track their consumption.

The research also measured a secondary result, which was assessed using a standard calendar log, that is common in AUD trials. This log tracks the number of drinks consumed per drinking day, the frequency of heavy drinking days, and weekly cravings, providing insight into participants' drinking behaviors and cravings over time. The primary result was measuring the alcohol intake in a lab-controlled environment after the treatment had been administered, while the secondary result was a constant assessment that the individuals had to measure themselves.

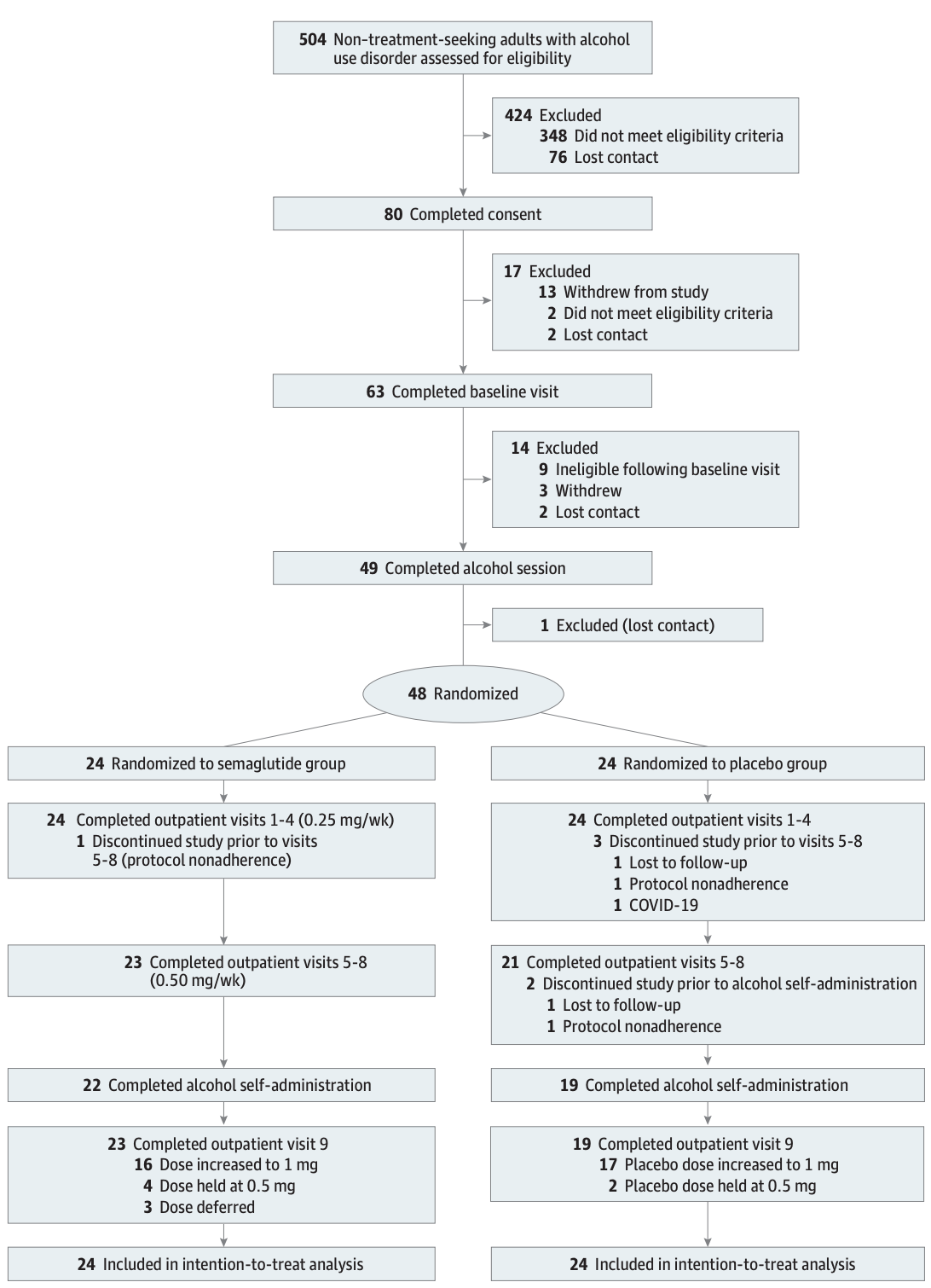

Forty-eight trial participants were chosen from a group of non-treatment-seeking adults with AUD. The group was randomly divided in half, with one group receiving an injection of semaglutide and the other receiving a placebo. The injections were given weekly and increased periodically after the individuals had outpatient visits to assess their health. The experimental group followed a dosage schedule of 0.25 mg/week for the first four weeks, 0.5 mg/week for the next four weeks, and 1.0 mg/week for the final week. However, since each dosage increase was determined during outpatient visits, only 16 participants ultimately received the full 1.0 mg dose. The same was done with the group taking the placebo; the detailed explanation on how many individuals had an increase in dosages can be found below:

Above: Selection of experiment consort flow diagram. Image courtesy of Hendershot, C. S. (2024). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical trial.

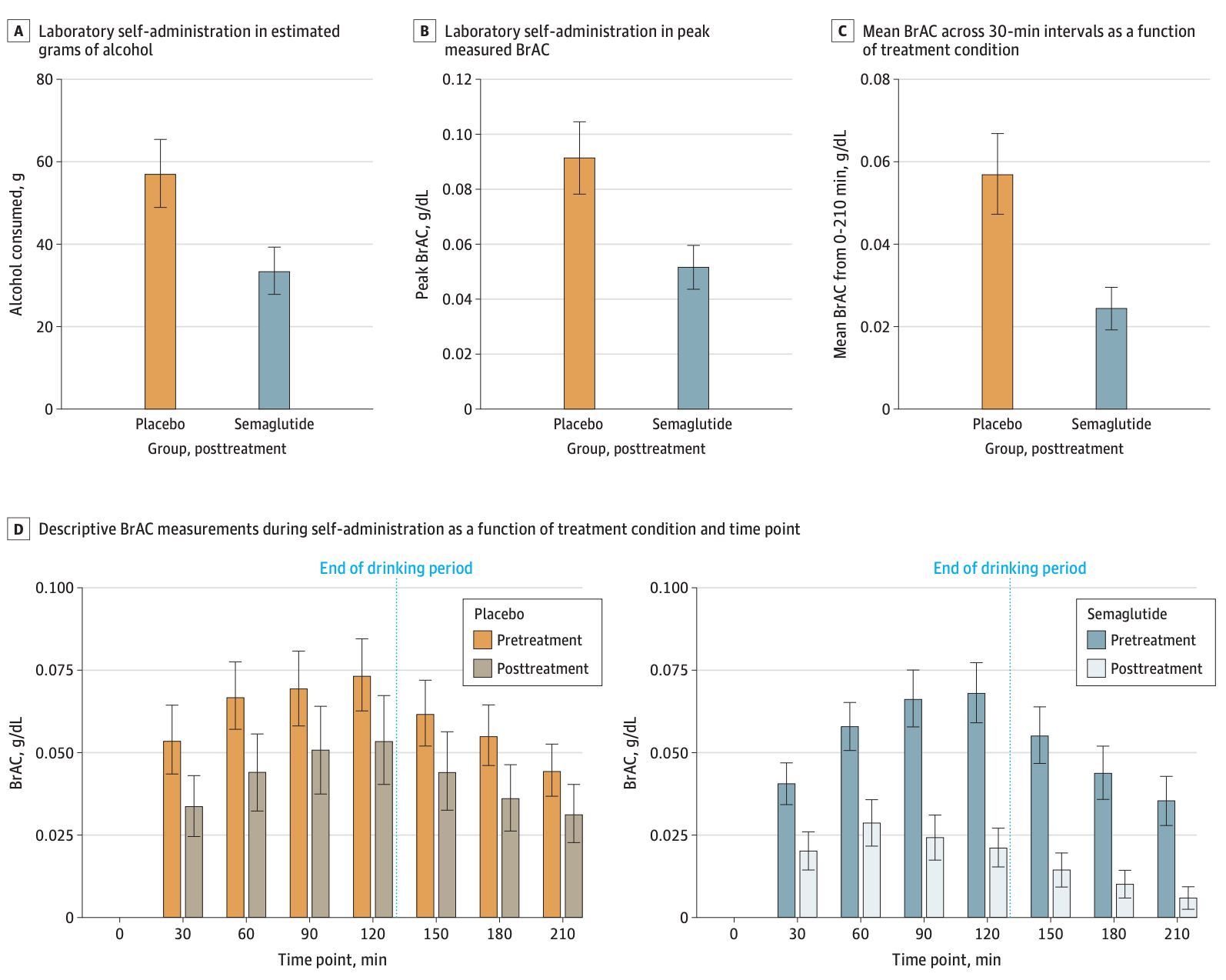

The results reinforce the previously noted anecdotal relationship between decreased alcohol consumption and semaglutide. By the end of the study, the group taking semaglutide drank almost 30% less alcohol on days they consumed. Moreover, looking at the alcohol consumed in the laboratory setting after the experiment had concluded, as shown in the figure below, those who took semaglutide had a decrease of 0.02g/dL in peak breath alcohol concentration (BrAC). A standard drink (beer or wine) increases a 150-pound individual’s (BrAC) by 0.02g/dL; therefore the semaglutide group drank one less standard drink than the control group.

Above: The BrAC levels for placebo and semaglutide groups for both primary and secondary results. Image courtesy of Hendershot, C. S. (2024). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical trial.

The trial results showed that semaglutide reduced alcohol consumption across all measured outcomes. The beta coefficients, indicators of the correlations between AUD and GLP use, were negative for all three outcomes (grams of alcohol consumed, peak breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) and mean BrAC), indicating a reduction in alcohol use.

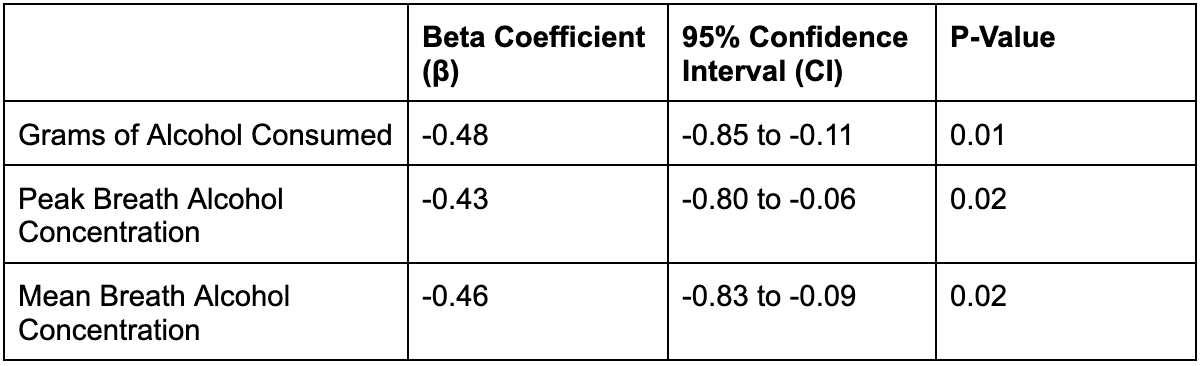

For a more detailed breakdown of the results, please refer to the table below.

Table of Results. Data sourced from Hendershot, C. S. (2024). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical trial.

The beta coefficient, which shows the direction and magnitude of the effect of semaglutide on alcohol use, is negative in all three outcomes, suggesting an overall reduction of alcohol consumption in all measurements, including the BrAC or estimated grams per alcohol consumed. The confidence interval represents the range within the true effect size is likely to fall with 95% certainty. The p-value represents the probability that the observed effect occurred by chance. The p-values are less than 0.05, representing a less than 5% chance of happening at random.

Although the results demonstrate a promising potential for Ozempic to decrease alcohol craving, researchers acknowledge the limitations of the small sample size and short duration of the trial. Longer and larger studies should be conducted to confirm these preliminary findings; however, these results suggest progress in the search for effective AUD treatments