Above: Venn diagram with MD and PhD on either side and a question mark in the center. Image courtesy of Blueprint.

A disheveled medical student finds themselves sprawled out on their couch; they’ve just spent the last fourteen hours of their Saturday studying for one of the most important exams of their career: the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE). Driven by a worrisome level of caffeine and that “guaranteed” six-figure salary, they persist nonetheless. However, the light at the end of their collegiate tunnel is further back than they realize, as an additional four years of graduate school await them before they can even finish their last two years of medical school. Lying exhausted on that couch, they can’t help but wonder, “Is this worth it?” This is the reality for thousands of MD-PhD students across the US.

The MD-PhD dual-degree pathway was established following the post-World War II rise in biomedical research in response to a national need for physician-scientists who can both treat disease and investigate its underlying causes. In the 1950s and 1960s, the National Institute of Health (NIH) spearheaded the first of these programs. In 1956, Case Western Reserve University established the first MD-PhD program, shifting the paradigm towards health professionals who could extrapolate their skills “from bench to bedside.”

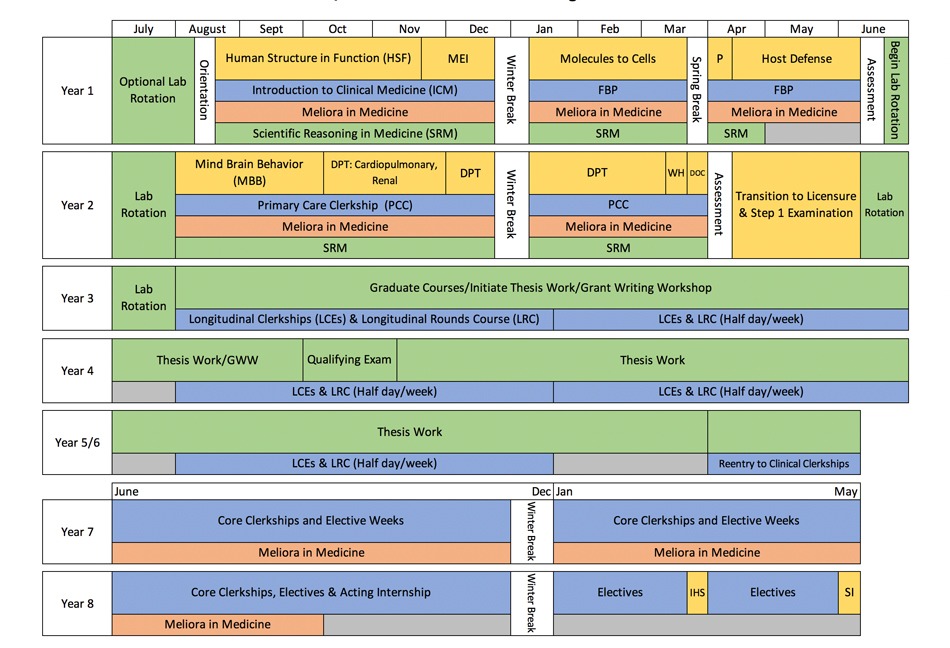

Today, the typical MD-PhD program takes around eight years to complete. Although schools across the country vary, the usual pathway consists of

- Years 1-2 (Medical School): Core medical curriculum (anatomy, physiology, etc.)

- Years 3-6 (Graduate School): PhD research, dissertation, and defense

- Years 7-8 (Medical School): Clinical clerkship, including rotations through various specialties (ex., Neurology, pediatrics, internal medicine, OB/GYN, etc.)

While completing school in your late 20s is already daunting to most, it may seem even more intimidating if you consider residency. In the case of a neurosurgeon attending their first year of undergrad in 2024 on the MD-PhD track, they can expect their last day of class in 2045! So, why is such a challenging pathway still considered?

Above: Typical MD-PhD eight-year plan. Image courtesy of the University of Rochester.

Double the Degrees, Double the Glory (Sort Of): The Advantages of MD-PhD

Above all else, there is one clear financial benefit as an MD-PhD: the program is fully funded by Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) stipends through the NIH. That is to say, the NIH covers nearly all MD-PhD students’ tuition, health insurance, and living expenses (a full-ride). Considering the average price of these expenses is projected to be upwards of $400,000 for a typical U.S. MD program in 2030, the 100% discount is hard to pass up. Moreover, the degree offers immense job flexibility, as universities significantly favor MD-PhD applicants in their hiring process. Similarly, research labs and hospitals overwhelmingly value the clinical and research expertise of the dual-degree. To many, MD-PhD is viewed as the pinnacle of a health science education, so there is little worry of job prospects post-matriculation. Of course, ambition’s price tag is one of dual measures: tuition and time. For the latter, this degree is by no means a full-ride.

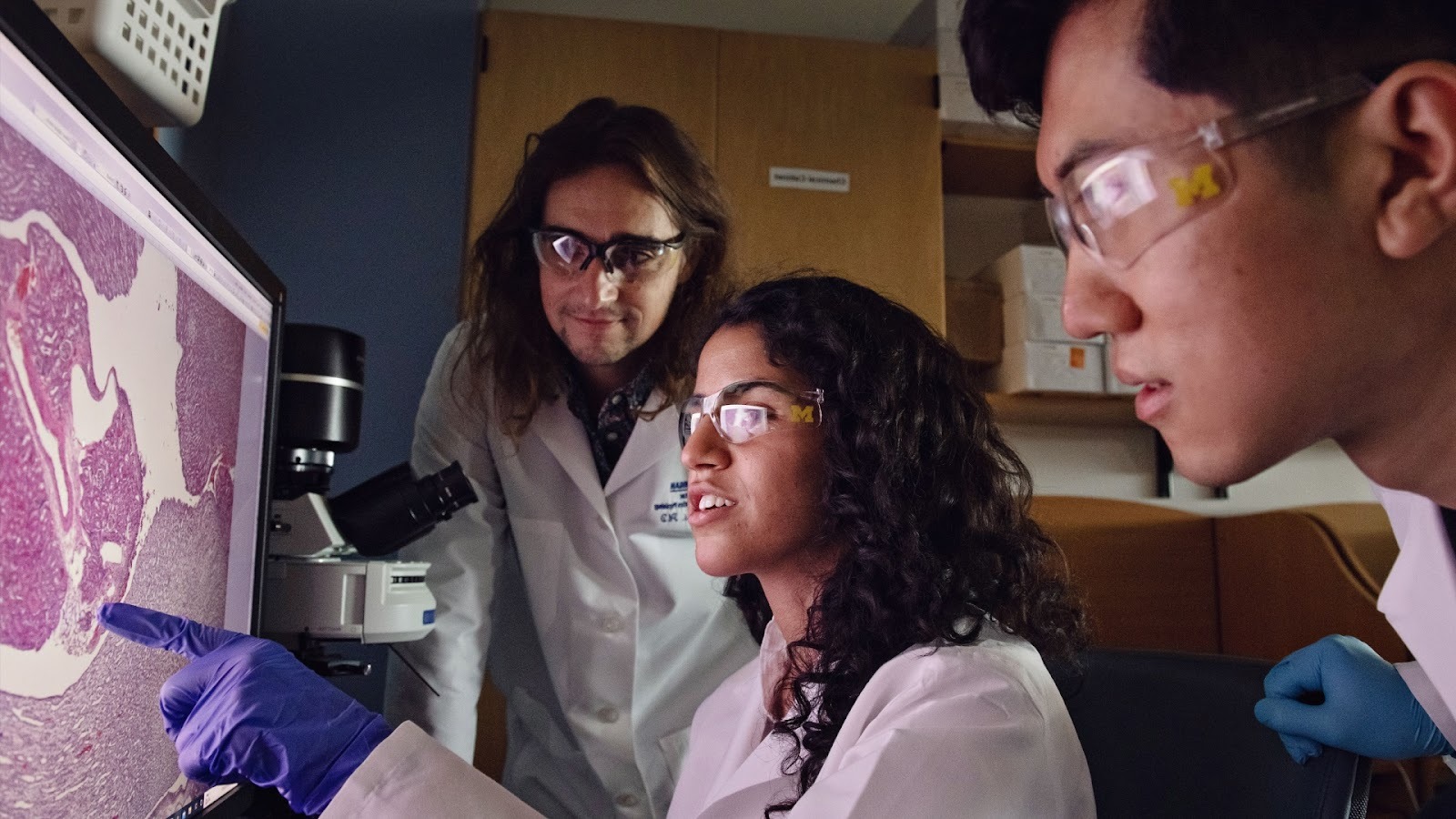

Above: Scientists analyzing a microscopy image of tissue. Image courtesy of the University of Michigan Medical.

Free Tuition, Expensive Life: The Drawbacks of MD-PhD

First and foremost, the MD-PhD program adds at least four additional years to an already laborious, lengthy career program. To many, the thought of being in your 30s and still not fully settled into one’s career is enough of a deterrent. The chance of burnout is immense for either degree individually, but it skyrockets when you consider the perseverance required to balance such different careers: clinician and scientist. Statistically, this concern is validated by the 27% yearly attrition rate for MD-PhD candidates. Further, most MD-PhDs tend to heavily favor one side of their degree, choosing to work nearly full-time in a lab or in the hospital, with most choosing clinical work the majority of their time. Hence, the payoff is not as “guaranteed” as previously mentioned arguments would suggest. Lastly, peers in pure MD or PhD tracks advance faster, thus profiting from their hard work much earlier in their careers. Speaking of one of these peers, the following interview with a current PhD student in his last year provides an outside, well-informed opinion for this discussion.

Above: Stressed medical student massaging her temples. Image courtesy of Tego Insurance.

Perspective from the Benchside: An Interview with a Duke PhD Student

Xiao Guo, a biomedical engineer in his fourth year of graduate school at Duke University, noted that much of his experience working with MD-PhD students arose through translational projects (those that aim to have clear health applications, such as treatments or diagnostics). Xiao underscores that these students “approach the problem from a clinical side,” which provides an invaluable perspective in the “understanding of a particular disease” or how it might apply to “a patient they see.” He even notes an example of an MD-PhD who was working on a potential cure for the same disease his patient was battling. Underscoring the notion that labs uniquely value this dual-degree, Xiao explains that he thinks “to have that perspective is powerful.” However, he also notes that there are many drawbacks, as it’s “a lot of time commitment” and “most [MD-PhDs] are a lot older” than their colleagues. Uniquely, he notes that “most have a preference [towards one of their degrees]”, which can be viewed in both a positive and negative light. On one hand, it means that you are not locked into a 50/50 balance as a physician-scientist, but are awarded considerable flexibility in your career. On the other hand, the second degree begins to feel superfluous if one is employed preferentially anyway.

Above: MD-PhD graduating class at The University of Toledo. Image courtesy of The University of Toledo.

Beyond the Acronyms: Is MD-PhD Worth It?

In the end, there is no clear answer as to whether this dual degree is “worth it”—a delightfully frustrating answer to an equally frustrating career choice. If you’re drawn to questions as much as cures, then there is no doubt that the cost of an extended education is outweighed by the rewards of flexibility, prestige, and fulfillment one can receive from an MD-PhD. That said, if your heart drifts more towards the clinic than the lab or vice versa, there is no shame in picking either of these commendable pathways. Additionally, healthcare does not exist in a bubble. In either career, you are bound to have endless opportunities to work with patients, form hypotheses, and lose yourselves in your curiosities. In knowing what’s right for you, ask not what letters you’ll earn, but the life you want to live between them.