A New Model for an Old Problem: Bioengineering the Path to Understanding Uterine Fibroids

Above: Dr. Erika Moore (middle) and trainees Lara Larson (left) and Ally Moses (right).

Situated deep within the smooth muscle tissue of the uterus, a single stem cell divides, quietly initiating a process that will affect 80% of African American women and 70% of European American women by age 50: uterine fibroid formation. While often unbeknownst to women at first, these typically non-cancerous growths, ranging in size from microscopic clumps to masses capable of filling the pelvis, can become profoundly uncomfortable.

Dr. Tricia Markusen, a practicing OB/GYN in Monterey, California, knows how disruptive uterine fibroids can be. Markusen explains that for many patients experiencing symptoms, their first step is a trip to the doctor. "Usually, patients present with symptoms of pain, urinary issues like urgency, pelvic pressure, or abnormal uterine bleeding," she notes. "It depends on the size and position of the fibroids. Sometimes, we detect them during a routine pelvic exam on patients who aren't even aware they have them. A large percentage of women get fibroids, and it causes major health and financial issues," Dr. Markusen adds, highlighting the real-world stakes.

Despite their prevalence, the mechanisms underlying fibroid development remain poorly understood. A leading hypothesis suggests that hormones like estrogen and progesterone indirectly support fibroid growth. Additionally, research shows growth factors such as growth factor-beta (TGF-βeta) and epidermal growth factor (EGF), which are stored within the uterine extracellular matrix (ECM), the structural “scaffolding” around cells, may further promote fibroid expansion. However, limited understanding has long hampered the development of effective, non-invasive treatments. Currently, fibroid studies rely on live tissue from surgeries, which is scarce and often loses viability after removal.

A 3D Solution For a Complex Problem

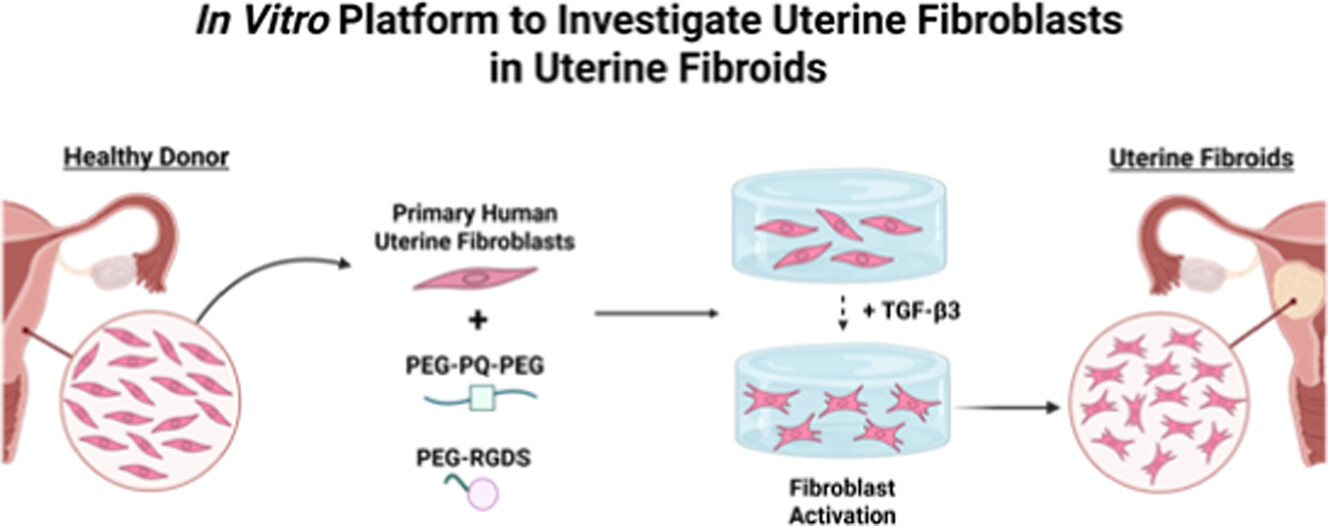

To address the lack of live tissue for research studies, Dr. Erika Moore’s team at the University of Maryland developed a novel 3D hydrogel model designed to mimic the fibroid microenvironment. This bioengineered environment recreates critical features like mechanical stiffness, ECM composition, and structure – all factors known to influence cell behavior.

Above: Dr. Moore, who was recently featured in Science News’ “2025 Scientist to Watch” series. Photo courtesy of Dr. Moore’s website.

To stimulate healthy tissue, the researchers embedded human uterine fibroblasts into polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based hydrogels, a type of polymer network. According to Wang et al., PEG hydrogels are easy to modify and known for their ability to trap and hold drug molecules. These characteristics allow scientists to grow a large number of models from a single cell donation.

To trigger fibroid-like formation, the researchers added varying concentrations of transforming growth factor (TGF-β3), an immune messenger called a cytokine that is known to drive fibrosis. Moore’s team then used a sandwich ELISA, a technique used to bind and measure protein, to assess whether the cells secreted or consumed TGF. Next, they performed a western blot to detect relative levels of LOX, an enzyme that cross-links collagen and contributes to tissue stiffness.

Above: Schematic detailing the method Dr. Moore's lab utilizes to study uterine fibroids. Image courtesy of Moses et al.

The study was a success: Moore’s team created a model that closely recreated the biological and mechanical environment of a developing fibroid. As the researchers imaged the fibroids, they observed increased expression of classic fibrotic markers. Over time, fibroblast behavior mirrored the progression seen in the body: proliferation decreased while collagen production increased. The detection of LOX confirmed that the model was not only producing collagen but that the right conditions were present to activate the mechanisms that stiffen it, driving the fibroblasts toward a fibroid-like state. Crucially, by inhibiting the TGF-β pathway (using the inhibitor SB-431542), they reduced collagen expression. This confirmed that beyond the physical stiffness of the environment, the biochemical signals (specifically TGF-β) are drivers of fibroid formation.

From the Lab to the Clinic

The study's most promising finding is that by inhibiting the TGF-β pathway, fibroblast activation can be stopped. This suggests that fibroid formation may be preventable if targeted early. Furthermore, Dr. Moores’s model can be recreated using primary cells from different patients. This allows scientists to test anti-fibrotic drugs or study patient-specific fibroid behavior.

This research is particularly significant given the clinical reality of fibroid treatment, which is far from one-size-fits-all. "Treatment is a 'shared decision' with the patient," Dr. Markusen emphasizes. The chosen path heavily depends on the patient's goals, especially regarding fertility. "For patients who wish to preserve their uterus, a hysteroscopy can remove submucosal fibroids... with a quick recovery," she notes. Other options to treat these gynecological tumors range from hormonal drugs which manage bleeding, to minimally invasive procedures that shrink fibroids, to a hysterectomy – the definitive solution but accompanied by the highest recovery time and inability to bear children.

This landscape of imperfect options highlights a critical reality: we are still treating the symptoms and the tumors themselves, not the underlying cause of why fibroids form. This is precisely why the bioengineered hydrogel model is so promising. "We have come a long way in treating fibroids since I started practicing," Dr. Markusen reflects, remembering a time when hysterectomy was the only solution for fibroids.

The model's ability to pinpoint the TGF-β pathway as a key driver opens a new frontier. It moves the goal from surgical intervention to molecular prevention. With this 3D blueprint, Dr. Moore and her lab are now collaborating with clinicians to understand why fibroids form and how they might be treated using non-hormonal small molecules to slow their growth. The hope is that one day, uterine fibroids will be a problem of the past.