By Ankit Biswas and Jack Chen

Above: The Simons Observatory at night. Photo courtesy of Hironobu Nakata.

Dr. Jenna Moore describes her work as “basically building really advanced Legos.” To say that description is an understatement would be an understatement in itself. Since 2018, Moore has built cryogenic instrumentation for the world’s most advanced and remote observatories, scanning the first light in the universe — the Cosmic Microwave Background — from high in the Andean mountaintops.

But Moore’s path to the stars has been far from conventional. As a child growing up in the rural outskirts of Charlotte, she displayed a knack for tinkering. Her eyes lit up as she described how her “dad would just hand me a hammer and a pair of nails and I would just hammer things together.” Grabbing whatever space-themed Lego set she could get her hands on, Moore began to build up an impressive collection of tens of thousands of pieces of Mars Rovers and Hubble Telescopes. As a teenager, Moore attended Olympic High School, specifically its math and engineering “mini-school,” taking a variety of engineering courses. But after she graduated, Moore felt lost.

Above: Moore testing components in her living room during the height of the pandemic. Photo courtesy of Dr. Jenna Moore.

Under the Sara Doll Burgess Scholarship, Moore decided to attend Queens University, where she majored in chemistry. Despite a school that hosted one of the world’s most preeminent future astrophysics instrumentalists, Queens University didn’t even have a physics department when Moore attended, save for one class in algebra-based physics. But it was here that Moore, who hadn’t even considered graduate school, decided to study the universe. During her senior year, she completed a research project building a small 3D-printed spectrometer. She stared into the distance as she recalled the memory: “I realized then that there was this whole career path for me to do science.”

Coming from a non-academic family, Moore wasn't planning on a future academic career until her research advisor asked her where she planned to attend graduate school. Encouraged by her Queens professor, Jenna applied to the Fisk-Vanderbilt Bridge Program in Nashville, a well-known program designed for students from small schools or those changing fields who want to pursue PhDs but don't have the traditional background to jump straight in.

At Fisk, she worked in a materials science group doing scintillator physics with crystal growth and radiation detection devices. There, she met someone who had just graduated from a research group focused on astronomical instrumentation. "That sounds even cooler," she thought.

Following the tip, Moore went to Arizona State University for her PhD in Exploration Systems Design, a specialized degree specifically for astronomical instrumentation. It was here that Moore participated in her first observatory build. She joined just as the Simons Observatory was transitioning from design to construction. Moore’s advisor, Dr. Philip Mauskopf, had an unusual mentoring style: he'd throw students into the deep end with zero training, believing in learning by doing. As a first-year PhD student who had never touched a coaxial cable, Jenna was handed a complex design for readout harnesses for these telescopes and told to "Figure it out, make it happen." Often she'd be working on something in the lab, then learn about it in class two weeks later and think, "That would have been nice to know earlier."

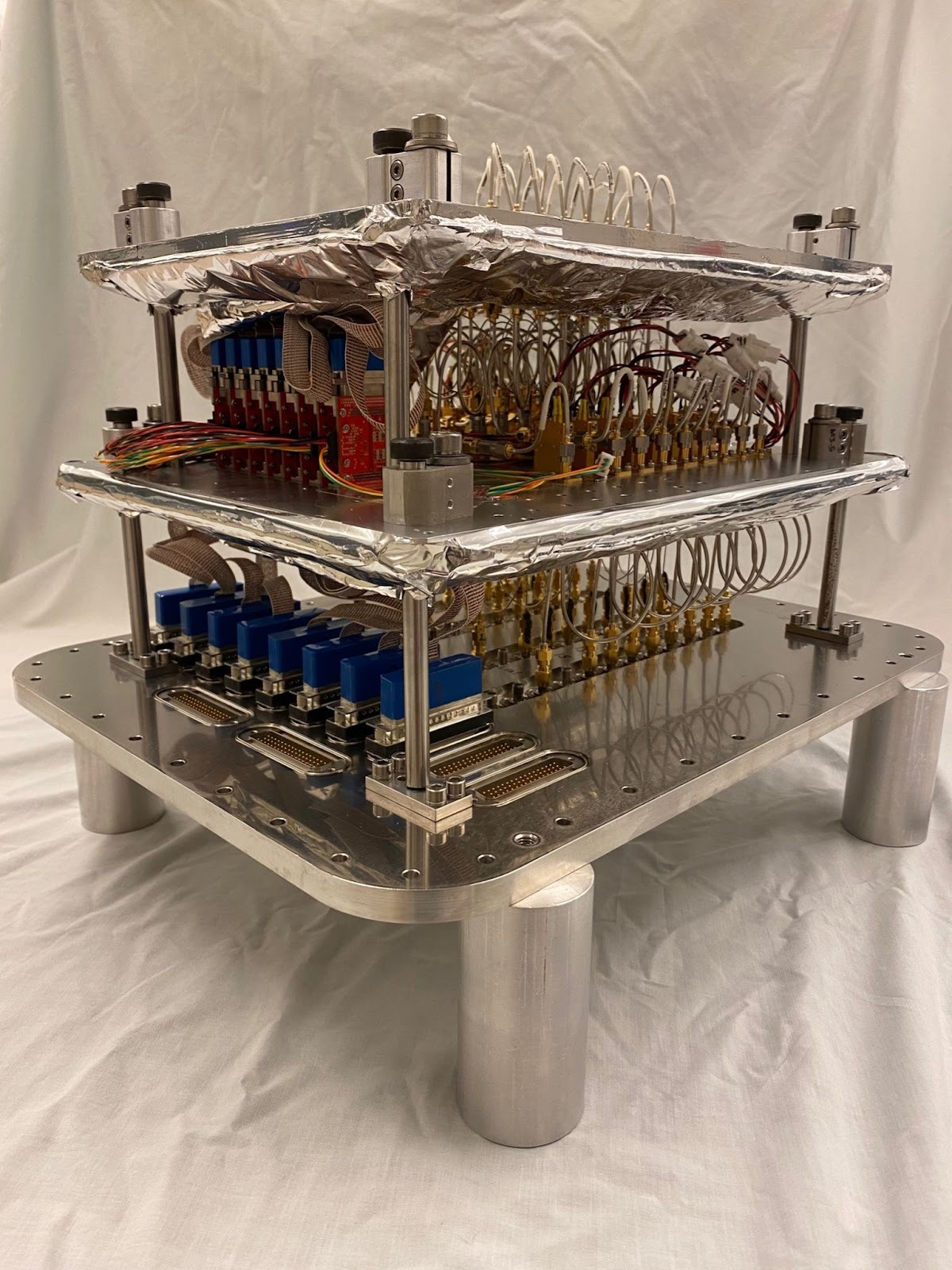

Above: Cryogenic research harness. Image courtesy of Dr. Jenna Moore.

Once Moore and collaborators built and tested the instruments in the U.S., they would travel high up in the Atacama Desert to integrate them with the telescopes. Despite its remoteness, the Atacama is preferred by astronomers around the globe, with its high altitude and extreme dryness creating exceptionally clear and stable air — as close as you can get to space without actually being in space.

Moore described the intense environment in the Andes: “I compare working on top of a mountain to the show Chopped, where you're thrown into an intense environment with limited resources, and you just have to think on your toes really fast.” Lamenting the lack of “Amazon same-day delivery on top of a mountain,” Moore recounts with vivid detail working in the Andes as she scrolled through photos from years past. The situation felt almost surreal to her as she looked around “And it's all just other grad students, and you're like, oh, ‘they really just sent a bunch of kids down to the mountain to put this thing together.’”

The final product, however, makes the struggle worth it for Moore. “My blood, sweat, and tears are on this... It's not just, like, a job that you had for a few years. It's, like, oh, no, that's, like, my baby.” The Simons Observatory has been fully operational since March 2025, with all four telescopes scanning the sky. The telescopes have over 60,000 detectors, more than all previous cosmic microwave background observatories combined.

Above: Moore at work. Image courtesy of Dr. Jenna Moore.

Throughout grad school under the arid heat of Phoenix, however, Moore missed the milder tempers of her North Carolina home. So it broke her heart spending “all of grad school, six years, trying to explain to [her] mom, look: I'm probably not going to ever go back home. I know there's a lot of universities in North Carolina, but none of them are actually doing what I'm in school learning how to do.”

Her lucky break came last year. Her PhD advisor, who happened to be from Durham and had attended the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, mentioned that Professor Eve Vavagiakis, a colleague from the Simons Observatory collaboration, had just been hired at Duke and was looking for a postdoc.

Moore’s response: "That's great. That's the wrong school [joking about the UNC-Duke rivalry]. But... she's looking for a postdoc?" But ultimately, she decided to reach out: "It's unfortunate that it's at Duke, but I'm looking for a job. If you want to talk about it, let me know." After a few conversations, it was clear they'd be a great fit. Jenna went home and surprised her family: "Guess what? I just got a job at Duke. So I'm moving back." Her family had no idea she'd even applied.

Now back in North Carolina after her "fun excursion" across the country, Jenna works in Duke's new lab, which Vabainakis established just over a year ago. As the first postdoc in a brand-new research group, she's been setting up infrastructure: assembling a dilution refrigerator, acquiring equipment, and creating new systems.

She's also involved in the CCAT Observatory project called the Fred Young Submillimeter Telescope, another Chilean telescope on a neighboring mountain at 18,000 feet. A graduate student who joined last year will have the same full-circle experience Jenna had, seeing a project evolve from design to data collection over the course of his degree.

After years in Phoenix where she couldn't garden due to the heat and her southwest-facing patio, Jenna now enjoys gardening again in North Carolina (though everything froze last winter). She keeps a photo of Leo, her childhood dog, on her desk, the same photo that got her through those strenuous first few years of grad school. She also has a picture of her elementary school, from which teachers as far back as first grade showed up for her dissertation defense.

Jenna sees her role as enabling measurements that advance human understanding of the universe. “As a human species, why would we not try and figure out how the heck we got here? And like, what are we doing on this rock? To me, I think that's just like part of the nature of being human is wanting to pursue those questions.” She hopes to stay at Duke for at least a few more years, though the uncertain funding climate (with recent cuts to NSF and DOE programs) makes long-term planning difficult. The field is increasingly relying on private funding from wealthy benefactors like the late Jim Simons and Cornell alumni.

But fundamentally, Moore’s driven by how much her work will help humanity understand the fundamental reality of our universe: "Something I helped construct or I built is literally going to tell us how the universe began. That, to me, is crazy. I went from some girl that grew up in Charlotte going to some tiny school. And now I'm doing all this crazy stuff."

Ankit Biswas is a senior at the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics interested in cosmology, AI, and science communication. When he’s not staring at the stars, he’s playing Quiz Bowl, reading a sci-fi novel, or listening to his 1000-hour Bollywood playlist.

Jack Chen is a junior at the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics with interests in engineering, computer science, and science communication. In his free time, he enjoys playing chess, cooking, and spending time with his friends.