You Have No Choice but to Read This Article: The Free Will Debate and Modern Neuroscience

In 1536, a Dutch physician authored a treatise arguing for the reform of witch trials, specifically the abolition of the widely used “tear test.” In this archaic test, an accused elderly woman would listen to the story of Jesus’s crucifixion, and if she did not cry, she would be declared a witch and executed. The physician argued that tear ducts in older women often atrophy with age, making it physically impossible to shed tears. Yet these women were burned at the stake. Biology, not sin, sealed their fate.

Famous Stanford neuroscientist Dr. Robert Sapolsky cites this example in his book “Behave” to illustrate how legal and moral judgments can lag centuries behind biological understanding – especially when it comes to human choice. In his newest book, “Determined,” Sapolsky further argues that free will does not exist. As we learn more about the brain, he writes, it becomes increasingly clear that behavior is shaped by our genes, experiences, and environment. Just as the elderly women subjected to the “tear test” could not shed tears even if they wanted to, many human behaviors may be less freely chosen than they appear, if at all.

Above: Dr. Robert Sapolsky. Image courtesy of Stanford University.

From choosing an apple over a banana, to burping loudly at a funeral, or even committing a crime, Sapolsky argues that an action taken in any given moment is the only act that could have taken place, much like how a ball that is thrown at a specific angle must land in a specific location. To truly understand behavior, Sapolsky insists we must consider everything that has ever happened to a person – from one second before, seconds to minutes before, hours to days before, across childhood, adolescence, and even in the womb. Sapolsky posits, “This notion of free will, for want of a less provocative word, is nothing but a myth. What's going to be really challenging though is to figure out how you structure a society that actually runs humanely built around the notion that we are merely biological organisms.”

The Illusion of Free Will in Everyday Choices

The debate about the existence of free will touches nearly every domain of human life, but two prominent areas of impact include addiction and learning. Consequently, this age-old debate is impacting the work of researchers such as Dr. Nicole Schramm-Sapyta, an Associate Professor of the Practice in the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences whose work examines the interplay between addiction and incarceration, and Dr. Minna Ng, Assistant Professor of the Practice of Psychology and Neuroscience who studies how learning environments shape student behavior and performance. Both professors have unique perspectives on how free will – or lack of it – impacts their research.

Above: Dr. Minna Ng (left) and Dr. Schramm-Sapyta (right). Images courtesy of Duke University.

When asked whether neuroscience takes a position on free will, Dr. Ng pushed back. “I don’t feel like neuroscience itself speaks to free will,” she explained, “philosophers probably think about that.” Dr. Ng reinforced the distinction that neuroscience is an empirical science, grounded in the scientific method. Answering the free will question would require an impossibly perfect experiment – one capable of controlling millions of variables across genes, development, environment, and moment-to-moment brain activity.

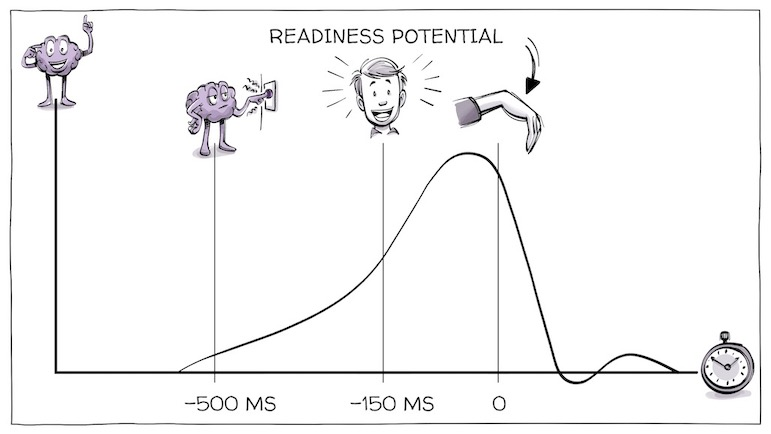

Nonetheless, scientists have prodded at these questions over several centuries. In a widely discussed experiment related to free will in 1983, Benjamin Libet measured readiness potential, a type of brain activity that occurs before voluntary movements. He found that brain activity preceded conscious awareness of the decision by 500 milliseconds, suggesting that unconscious processes drive behavior before we “choose” to act.

More recently, Soon and colleagues used functional MRI scans to predict people’s decisions up to seven seconds before they were consciously aware of them. Another study, Fried et al., found that neuronal activity in the brain could predict decisions up to 1.5 seconds before conscious awareness. This evidence challenges free will by suggesting that our conscious choices, at least small-scale ones, are not the starting point of behavior but rather an illusion of agency. However, Dr. Schramm-Saptya advised caution and described these experiments as “thin,” noting that their small-scale cannot be applied to the bigger life choices that we associate with free will.

Above: A depiction of Libet’s results showing that the action potential fired before human conscious awareness of the behavior. Image courtesy of Pascal Gaggelli for SproutSchools.com.

Although its existence has not been proven empirically, Dr. Schramm-Sapyta added that the absence of free will is not an unrealistic possibility. “A lot of our neural structure is genetically determined, and we didn't choose our genetics,” she explained. “The sensory input that we get as babies determines how we were wired, and the things we learn along the way tell us how to react to certain situations.” In this sense, Dr. Schramm-Sapyta said that it’s not a stretch to say that a lot is predetermined.

Dr. Ng saw behavior and choice differently. “I believe that biological mechanisms give us the structure by which to make some choices, whether it's driven from altruism or because you're hungry or because you kind of just pissed off at that person that you just want to smack upside the head,” she joked. “There's a control panel, but everyone's is different, and it's always changing. How is that different from any motor activity in the brain that belongs on a spectrum? The [control panel] knob, [take altruism for example], turns really far to the right in some people, and just a little bit to the right in other people.”

Overall, Dr. Ng and Dr. Schramm-Sapyta agreed that much of human behavior is calibrated differently based on life experiences with privilege, trauma, opportunity, and the ongoing feedback from our environment. “We're realists,” Dr. Ng stated. Regardless of how much behavior is determined, the fact that complete freedom of choice, commonly known as libertarian free will, does not exist should change the way we treat and perceive each other as human beings.

Free Will, Social Issues, and Equity

When it comes to addiction, questions of free will often come down to one issue: why some people are more vulnerable than others. For many scientists, it seems plausible that this vulnerability is predetermined. During her training, Dr. Schramm-Saptya explained she had implemented behavioral screens where she conducted five or six tests in rats and assessed which animals took the most drugs. “Individual differences on a very experimental, simplified operational level led me to say I can predict a little bit, but there's always error,” she added. “Hypothetically, if we could know everything that mattered to a decision, yeah, we could predict everything with pinpoint accuracy and have a perfect model.”

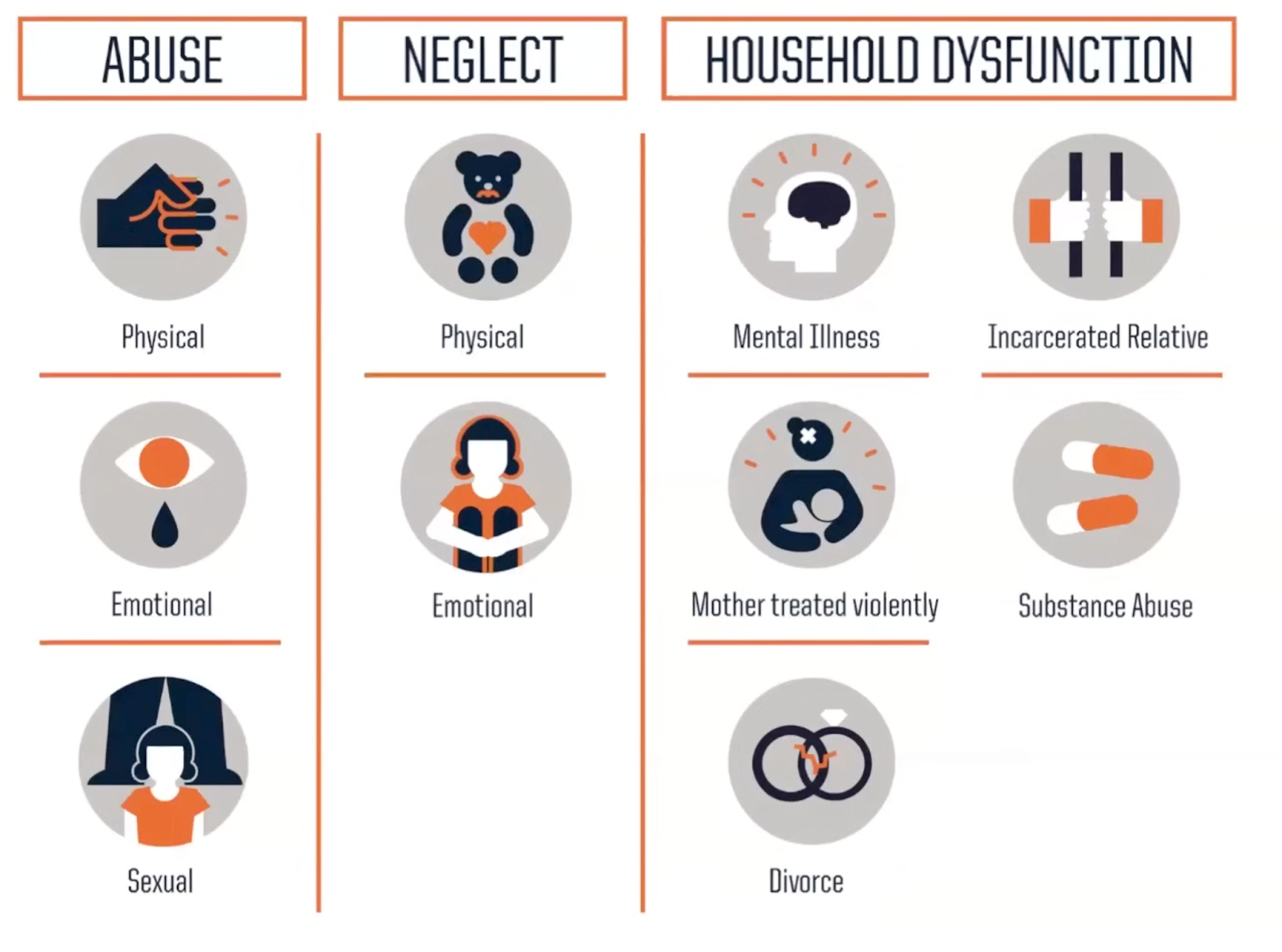

The idea that every behavior can hypothetically be predicted is central to Sapolsky’s “Determined.” In the book, Dr. Sapolsky cites Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) scores as being strong predictors of specifically whether or not a person is incarcerated at some point during their life. For example, he explains that around 98% of incarcerated individuals have at least 1 ACE point, and 45-60% have up to 4+ ACE points. This data, alongside the high prevalence of traumatic brain injuries among the incarcerated, prompts Sapolsky to urge us to apply this pattern of predictability to all human behavior, including the variables we cannot easily categorize like an ACE score, and approach people’s behavior with more compassion. He even advocates for criminal justice system reform that steps away from blame-based punishment (rooted in “mammalian revenge”) to one focused on rehabilitation and understanding.

Above: A list of the adverse childhood experiences that make up the total ACE score. Image courtesy of Dr. Sapolsky’s online lecture.

The approach Sapolsky advocates for is one both Drs. Ng and Schramm-Saptya discuss in Biological Bases of Behavior, an introductory class taken by many Duke undergraduates studying neuroscience. The biopsychosocial model of behavior emphasizes the interconnection between biology, psychology, and socioenvironmental factors. Both professors apply this model to their research.

Dr. Schramm-Saptya added that discussions about free will and the influence of biological, psychological, and social factors make more room for empathy when it comes to stigmatized topics like addiction. “We can do things to create conditions to support better outcomes for people. And in my own work with imprisoned people and people with drug addiction, they might not have chosen to get addicted to that drug. They might not have chosen a life in which the behaviors that help them survive in the street are the same behaviors that got them incarcerated,” she explained. “What you're describing, [Sapolsky’s ideas about reform], takes it to the next level, being societal. And can neuroscience destigmatize us from moral judgment? I think yes,” she said. “The fact that we've got a language around this, it helps us recognize the forces that have shaped us and recognize the forces that have shaped other people, and so to be able to say you're a product of a whole lot of things, some of which I can name, some of which I can't, brings us back to the question of, why are we here?”

Dr. Ng related this topic to her newly-created Constellation course, Understanding Neuroscience & Education, which explores the key question, “How can my education cause trouble and joy?” With all these behavioral influences coming together, Dr. Ng’s Constellation addresses how mistakes and setbacks can be valuable learning experiences. She wants students to think, “I learned something [and] that means I [exposed] myself to something that expanded me a little bit or made me feel something.” She wants students to know they are capable. When asked if she believes students would perform differently if they believed in free will or not, she responded, “We can always ask about free will. This is why people are going to be writing books like this for thousands of years and making plenty of money off of it. I think I would just walk away from that question altogether.” She added, “I believe very simply that students will perform better generally if they feel important and they feel that the person sitting next to them is important.” Dr. Ng explained that from her perspective, students perform better when they can explore and follow their passions. Dr. Ng’s point of view adds nuance to the free will debate, suggesting that an even greater benefit to society than debunking free will resides in supporting each individual’s sense of identity and belonging. In other words, the validation to explore (whether determined or of free will) is liberating and advantageous.

Religiosity and Biases

Both researchers also commented on another aspect of Dr. Sapolsky’ work: religiosity. In one lecture, Sapolsky posits that a link exists between religious rituals or belief systems and the traits seen in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). These similarities suggest that religious rituals may have originated as a way to manage anxiety through repetitive behaviors. He argues that behaviors and thought patterns that are maladaptive in a secular context are often protected, rewarded, and institutionalized in religion. “Get it wrong, and we call it a cult. Get it right, in the right time and the right place, and maybe, for the next few millennia, people won't have to go to work on your birthday.”

Dr. Schramm-Saptya responded, “It's not a hard thing to say that religious rituals have an OCD- like quality, and that goes back to the same question you brought up earlier: does [acknowledging this connection] do us any good as a society? Yeah, maybe, right. Does [religion] make us feel connected? Yeah.” Dr. Ng chimed in, “Now, where does it possibly become a problem? If you are important and you think that that's important to you, then do it. But if now you suddenly think that your neighbors [who aren’t] getting the Eucharist are [less] important, that is dangerous. Because it's not just your air that you're breathing. You're breathing everybody else's air too.” Dr. Ng connects this idea back to her statement on the benefit of feeling important and how when we see our peers as less than, we create a dangerous dynamic.

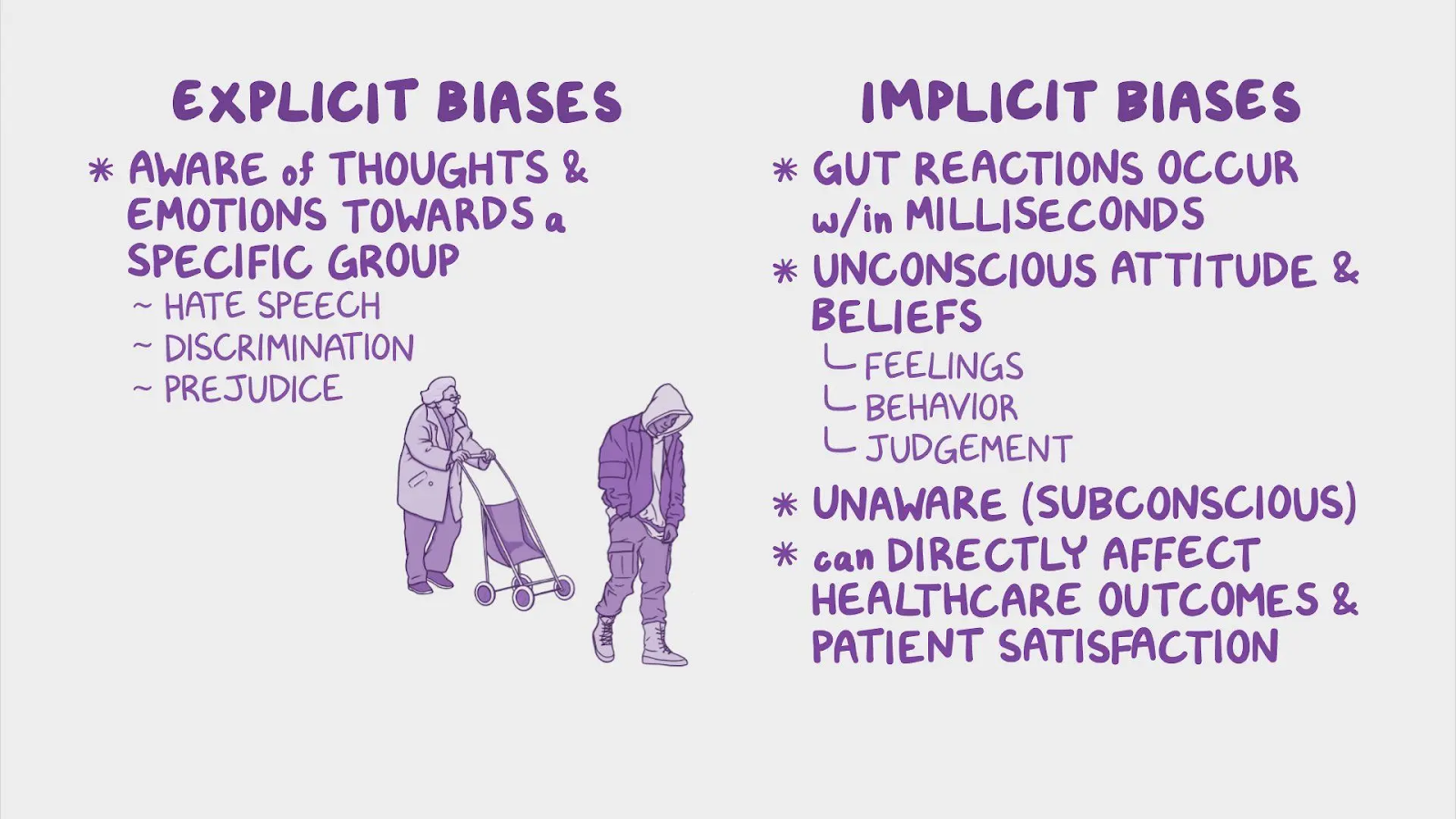

Sapolsky argues that religiosity is just one way we categorize our relationships with others into "Us" and “Them” (or in-group vs. out-group). Dr. Schramm-Saptya explained that in-grouping and out-grouping help us survive but is a behavior often taken too far. Both professors then discussed the well-known and widely used Implicit Association Test (IAT), an assessment of unconscious biases which is available online through the non-profit organization Project Implicit, a collaboration between researchers at Harvard University, the University of Virginia, and the University of Washington.

Above: Visual aid contrasting explicit and implicit biases. Image courtesy of Osmosis from Elsevier.

Dr. Ng explained that an issue arises when people carry out explicit behaviors as a result of implicit biases. “It comes back to this debate about free will in neuroscience. We should be aware of implicit biases, and then we can control them a little bit better, right? And if we are not so aware of them, then we just let it run wild,” she warned. “So far, the studies that I'm aware of [suggest that] when you are aware, you pause for a second, and maybe you'll make a slightly different decision. But we have to take time. We have to pause. So thinking very practically, we have to learn to stop and pause and think and question. And I think that that's something we need in our current educational system.” She added, “In our current digital age, there's no time to pause, to think, to answer those very, very key questions that guide your behavior and shape your control panel.” She says she aims to encourage students to pause and think before acting.

Even though free will’s existence has not been definitively proven nor disproven, discussing it may help steer questions about social stigma and hierarchies. Put simply, Dr. Ng states that “We can use a lot of humility; we don't need to find everything out because we won't. We have to recognize that everybody else has their importance. We don't know what we don't know.” For now, we can (or maybe cannot) still choose to care for each as much as we can and be aware of both the troubles and joy we encounter every day and have compassion for the ways we are all unique from one another.